Social

Contattaci

Indirizzo

Fondamenta Cristoforo Parmense 10 Murano VE

30141

Nitidezza di spazi, equilibrio e felice allusione alla solitudine

Olocausto

Doves

Modella

Al chiar di Luna

Fede

Da decenni, silenziosamente e in maniera appartata, Giampaolo Ghisetti, veneziano di nascita ma muranese d’adozione, ha condotto una personale ricerca nel campo della pittura, le cui coordinate critiche sono state lucidamente delineate da Paolo Rizzi nel 1978, in occasione della prima esposizione nella prestigiosa Galleria Santo Stefano di Venezia e nel 1993, ad introduzione di un catalogo.

Oggi manca da definire l’itinerario successivo a questi scritti, il cui compito, nell’osservare le opere più mature dell’artista, mi è stato affidato.

E’ necessario premettere che Giampaolo Ghisetti è riconosciuto in tutto il mondo come maestro decoratore del vetro, attività che implica una rigorosa autodisciplina e il saper conferire ad ogni gesto la sapiente tradizione dell’incisione, Con lo stesso riguardo, con uguale serietà, Ghisetti dipinge e scolpisce (le capacità in quest’ambito sono addirittura sorprendenti ) potendo contare su di una solida esperienza e una approfondita conoscenza delle tecniche pittoriche.

Nell’osservare la prima fase dell’artista muranese, all’incirca dalla metà degli anni Settanta sino ai primi anni Novanta, si riconoscono diversi elementi formali e stilistici che suggeriscono la sua adesione a dei principi e valori che appartengono per sensibilità ad una pittura “alta” , lontana dall’evocare personali accadimenti. Sono soggetti silenziosi, velati di una nostalgia antica per la pittura quattrocentesca, per quell’insieme di regole prospettiche che ritroviamo in pittori come Piero Della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, Mantegna; ma più ancora i riferimenti culturali si spostano al principio del Novecento quando, negli anni Venti, artisti come Virgilio Guidi, Antonio Donghi, Anselmo Bucci, Felice Casorati, arrestano il procedere delle avanguardie per ritrovare nella pittura dei loro predecessori toscani l’origine plastica della luce e il suo potere trasfigurante.

Sono quadri quelli di Ghisetti, in cui le forme si enucleano con chiarezza e rigore prospettico, come in S. Michele, oppure in Natura morta con uova (fig. 4), chiaro esempio, quest’ultimo, di un’intesa perfetta tra forma e luce. Da questi soggetti risulta evidente il legame tra Ghisetti e la cultura figurativa degli anni Venti del Novecento, in particolare quella di Felice Casorati ma anche del nostro Guido Carrer, per la nitidezza di spazi geometrici, l’equilibrio delle forme, la felice allusione alla solitudine. E’ una pittura che invita alla riflessione, e nella pacata armonia dei toni pastello s’infonde omogenea una luce che riveste d’incanto ogni cosa.

Le nature morte, così come i paesaggi, risentono di un clima che si è detto essere assorbito dai valori plastici del neo-quattrocentismo italiano e ravvisano, come in La valesana del 1991 (fig. 5) quelle suggestioni d’incantamento metafisico ( comuni anche a Cagnaccio di San Pietro, per rimanere in ambito veneziano) tali da avvicinare la pittura di Ghisetti al permanente mistero di quella stagione pittorica denominata “ realismo magico”.

Sin qui le nature morte e i paesaggi, ma basti osservare i quadri di ampia dimensione, quelli che includono monumentali figure umane per riconsiderare ancora una volta le analogie formali con il passato. Si prenda in considerazione Deposizione ( fig. 6) del 1992, e vi si osservi la concezione plastica dei corpi così attinenti alle forme scultoree e muscolari di un Signorelli o alle imponenze di un Masaccio.

Non si tratta di individuare in Ghisetti le tracce e i riferimenti che permettono delle similitudini stilistiche e compositive con altri pittori, questo diventa un gioco facilmente utilizzabile per ogni artista, anche i più grandi- anche Picasso fu suggestionato da Cezanne o dal classicismo italiano – ma semplicemente si vogliono lineare le appartenenze culturali, più ancora che stilistiche, verso un insieme di contenuti narrativi che ancora oggi è possibile interpretare.

C’è un momento nella pittura di Ghisetti, che è di passaggio tra l’essenzialità formale del primo periodo e lo stravolgimento cromatico ed espressivo degli ultimi anni. Questo passaggio è esemplificato da un’opera Pietà ( fig. 7) che èla variante successiva della Deposizione del 1992; pur presentando uguale struttura compositiva, distinti sono i valori stilistici e cromatici che le accomunano.Se nel quadro precedente le figure apparivano cristalline e la loro vitalità risultava sospesa ora invece i corpi si scaldano, i muscoli diventano elastici, i soggetti prendono vita, Ghisetti immette in quelle masse gelide un soffio vitale, e avvia la loro esistenza. Lo fa attraverso una pittura che scioglie, che traspira, che introduce in circolo ossigeno; lo attua con un gesto pittorico meno distensivo, più corto e accelerato, un colore più vario e materico. E’ una pittura dai sintomi espressionistici, tintorettiana e allo stesso tempo monumentale, con quel suggestivo insieme di contrasti chiaroscurali che immergono lo spettatore in un sogno.

E’ forse la fase più interessante del pittore muranese, quella più ricca di variazioni, quella più introspettiva e attraverso la quale Ghisetti prende a pretesto il proprio autoritratto per porsi delle domande dal come in Chi siamo ( fig. 8), oppure costruendo un percorso meta pittorico in cui si sposta dall’interno del quadro al suo esterno. Al cavalletto ( fig. 9) egli si rappresenta seduto intento a dipingere se stesso da vecchio, invitando così lo spettatore a riflettere sui molteplici rimandi che offrono le “ immagini raddoppiate” .

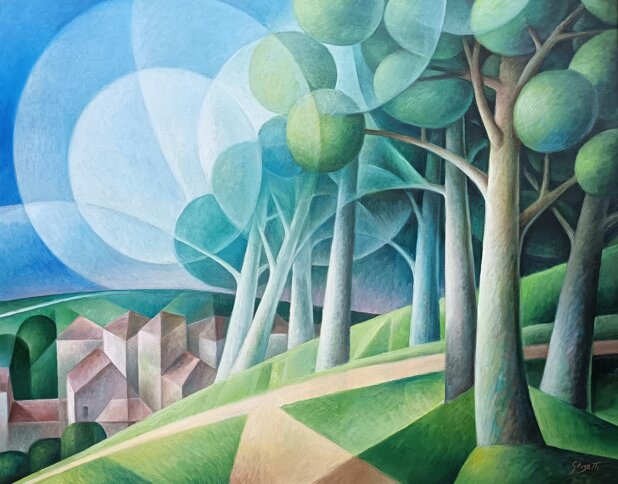

L’orientamento successivo di Ghisetti, quello che definiamo attuale e che comprende avvio dal principio degli anni Novanta, stabilisce un ulteriore livello espressivo e l’analisi critica deve ora tener conto di nuovi paradigmi stilistici e significative analogie con le avanguardie storiche del cubismo e del futurismo.

Opere come Olocausto, Amanti a Venezia e il Giudizio di Paride diventano esemplificative proprio in ragione della trasformazione plastica delle forme condotta attraverso l’esercizio del cubismo analitico. Ghisetti tende a mostrare l’oggetto nei suoi molteplici aspetti, analizzando in ogni sua parte, compattando la materia dei corpi in volumetriche geometrie.

Maternità (fig.10) evidenzia tutti gli elementi specifici della contrazione cubista accentuando inoltre il valore espressivo attraverso un dinamismo cromatico di origine futurista.

E a questo punto vale la pena di osservare lo stesso tema affrontato molti anni prima. Allora si trattava di evocare l’imperturbabilità di un momento, il sereno assopimento del bimbo che si nutre al seno della madre, ravvisando nell’iconografia un insieme di significati e contenuti prossimi alle “ Madonne con bambino” di origine quattrocentesca piuttosto che attinenti all’irregolarità dei colori e alle scomposizioni cubiste delle ultime ricerche.

In questa fase si arricchiscono i valori cromatici che virano verso timbrature decise e metallescenti inasprendo i caratteri dei soggetti che accumulano energia pronta ad esplodere in un insistente dinamismo come nel quadro Sopraffazione ( fig. 11), l’esempio forse più riuscito di un insieme di soluzioni ( dal movimento futurista alla molteplicità di piani cubisti) che esprimono la violenza prevaricatrice dell’uomo attraverso un contenuto e una sintesi plastica di elevata suggestione. I corpi, con l’irruente forza del loro dinamismo sconquassano l’ambiente circostante generando ridondanze spazio-temporali che sembrano trascinare con sé al di fuori del quadro.

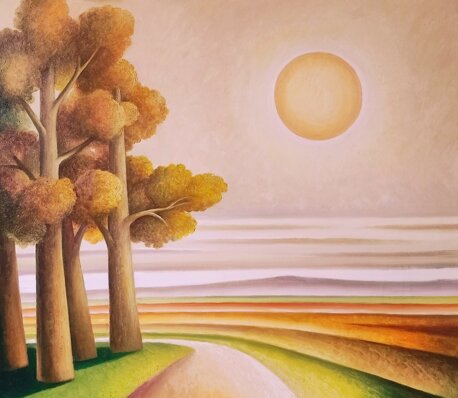

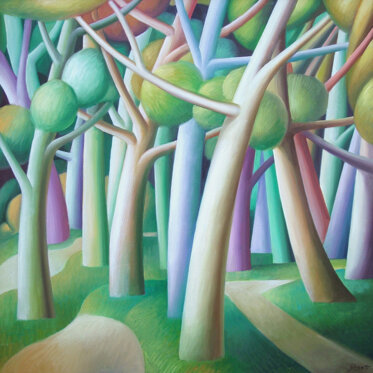

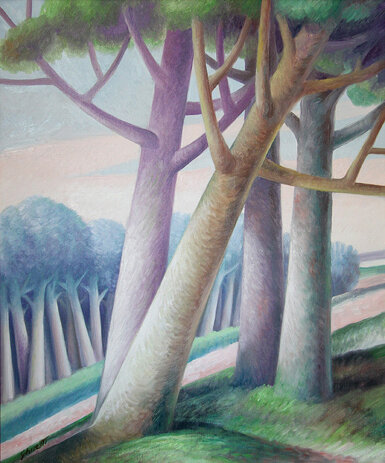

Di diverso tenore, quasi a voler mitigare l’inasprimento di certe forme umane, Ghisetti movimenta, con sinuose pennellate dal ritmo curvilineo, paesaggi dal sapore fiabesco. Si tratta, come in Paesaggio d’estate, Il bivio o La Strada, di un momento ulteriormente nuovo nella pittura dell’artista. Ora le forme non subiscono la cadenza geometrica tipica del cubismo ma si ammorbidiscono, flettono docilmente incuranti di ogni linearità prospettica, si espandono accrescendo di volume e di superfici non più terse e spaziose ma concentriche e ondulanti. La materia pittorica si fa più densa, il tratto dipinto più visibile e breve, trasfigurando il reale in accenni visionari dal carattere espressionista. In questo contesto Ghisetti inserisce una o più figure umane che, come nel quadro La Meta ( fig. 12) vengono ipnoticamente attratte dal concentrico movimento del sole verso un’ideale mondo spirituale.

E’ comunque una pittura che non si attiene al reale, che non riproduce la natura oggettiva delle cose ma che tenta attraverso un impegno autentico e originale, di cogliere le relazioni più segrete e sottili che legano l’essere umano con il mondo inteso quale potenza creatrice. Se la serie degli autoritratti sembrava incarnare un bisogno esistenziale che accomuna tutti gli uomini, quello cioè di porsi degli interrogativi sul senso della vita, sul proprio destino, sul significato della fede, sulla religione, ora invece con i dipinti più recenti l’artista ripone piena fiducia nella natura e nell’insondabile suo segreto.

Con il lavoro degli ultimi anni forse Ghisetti ci vuole comunicare che l’uomo da solo non è in grado di risolvere i grandi paradigmi dell’esistenza, che anzi l’essere umano è troppe volte orientato a coltivare gli aspetti più deteriori della vita, valga per tutti l’esempio di Olocausto la cui espressività degenera in un grido di dolore ammutolito nell’eterno, quasi a stigmatizzare il carattere universale e irripetibile di quell’evento.

Insomma Ghisetti alterna le vicende esistenziali dell’uomo moderno esemplificando la duplicità del suo agire: da un lato l’intenzionalità del male, la sopraffazione, la crudeltà; dall’altro l’intesa pacifica, la solidarietà, la fiducia nel futuro. Sono duplici aspetti che appartengono all’essere umano e che Ghisetti ha forse raffigurato metaforicamente con due soggetti ( Il giorno e la notte e Sacro e profano ) che potrebbero suggerire la presenza nei comportamenti umani di luci ma anche di ombre.

Attraverso la sua pittura più carica di speranza ( Colombe, Insieme, Dance e tutta la serie di paesaggi, compresi gli ultimi in ordine di tempo: Colle Santa Lucia, Primavera e Bosco incantato) crediamo che l’artista muranese contribuisca e auspichi lui stesso l’approssimarsi di un’epoca che sia il meno possibile contrassegnata dall’incomprensione e dalla prevaricazione. Se negli anni settanta e ottanta le forme ottenute dall’espandersi omogeneo delle superfici cristallizzavano gli eventi in una temporalità indefinita ora invece le opere di Ghisetti accentuano il proposito alla vita, ampliano lo spazio dinamico e nel rivolgimento delle figure non ritroviamo più la loro evanescenza ma il calore animico che ne rinnova l’esistenza.

Michele Beraldo

Summer

Il bacio

Walking

Maternità

Concertino cm. 120x150

For three decades, silently and securely, Giampaolo Ghisetti, born Venetian but Murano's adoption, conducted a personal research in the field of painting, his critical coordinates have been lucidly outlined by Paolo Rizzi in 1978 at the first exhibition in the prestigious Venice Santo Stefano Gallery and in 1993, with the introduction of a catalogue.

Today the path following these writings is missing. This task, in observing the most mature works of the artist, was entrusted to me.

It is necessary to state that Giampaolo Ghisetti is recognized worldwide as a decorator of glass, an activity that implies strict self-discipline and the ability to give in every gesture the wise tradition of engraving . Similarity, with the same discipline, Ghisetti paints and sculpts (the abilities in this field are even astounding ), relying on a solid experience and in-depth knowledge of pictorial techniques.

In observing the first phase of the Murano artist, approximately from the mid-seventies to the early 1990s, various formal and stylistic elements are recognized that suggest his adherence to the principles and values that pertain to sensitivity to a painting " high ", far from evoking personal events.

His are silent subjects, obscured by an ancient nostalgia for painting in the fifteenth century, for the set of prospective rules that we find in painters such as Piero Della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, Mantegna.

Cultural references move to the beginning of the twentieth century when, in the 1920s, artists such as Virgilio Guidi, Antonio Donghi, Anselmo Bucci, Felice Casorati stop the progress of the avant-gardes to find their predecessors in Tuscanys light and its transfiguring power.

These are the figures of Ghisetti, in which the forms evolve with clear perspective and rigor, as in S. Michele, or in Still Life with Eggs (Figure 4), a clear example of the perfect combination of form and light. From these subjects is evident the link between Ghisetti and the figurative culture of the 1920s, particularly that of Felice Casorati but also of our Guido Carrer, for the sharpness of geometric spaces, the equilibrium of forms, the happy allusion to solitude . It is a painting that invites reflection.

In the smooth harmony of the pastel tones is a homogenous light that envelops all things.

The dying nature, as well as the landscapes, are affected by a climate that has been said to be absorbed by the plastic values of the Italian neo-fourteenth centuries. In the La valesana of 1991 (fig.5) those metaphysical enchantments in Cagnaccio di San Pietro, to remain in the Venetian domain) draw Ghisetti's painting to the permanent mystery of that pictorial season called "magical realism".

Hence nature landscapes and landscapes, but watch out for large-scale paintings, those that include monumental human figures to reconsider the formal analogies of the past. Take into account Deposition (Figure 6) of 1992, and observe the plastic conception of bodies so relevant to the sculptural and muscular shapes of a Signorelli or to the dimensions of a Masaccio.

It is not about finding traces and references in Ghisetti that allow stylistic and compositional similarities with other painters.

This becomes an easily used game for every artist, even the most prominent ones, they simply want a linear culture, rather than stylistic membership to a collection of narrative content, that can still be interpreted today.

There is a moment in the painting of Ghisetti, which is a passage between the formal essence of the first period and the chromatic and expressive twist of the last years. This passage is exemplified by a Pietà work (Figure 7) which is the next variant of the Deposition of 1992; while the presenting same compositional structure are the scene the stylistic and chromatic values are distinct.

If in the previous picture the figures appeared crystalline and their vitality was suspended now instead the bodies warm up, the muscles become elastic, the subjects come to life.

Ghisetti enters in those frozen masses a vital breath, and begins their existence. He does it through a melting, breathable painting that introduces oxygen into the circle; it implements it with a less distorting, shorter and accelerated pictorial gesture, a more varied and material color. It is a painting with expressionist, tintoretic and at the same time monumental symptoms, with that evocative set of chiaroscuro contrasts that immerse the spectator in a dream.

Perhaps the most interesting phase of the Murano painter, the most varied one and the most introspective is that through which Ghisetti takes on his self-portrait for questions from how in Who we are (Figure 8).

Likewise by building a path a metaphor which moves from inside the picture to its exterior. At the stand (figure 9) he is depicted sitting to paint himself from the old, inviting the spectator to reflect on the many references that offer "duplicate images".

Ghisetti's later orientation, which we see today and which commences from the beginning of the 1990s, sets a further level of expression, and critical analysis it now takes into account new stylistic paradigms and significant analogies with the historical avant-garde of Cubism and futurism.

Works like Holocaust, Lovers in Venice and the Judgment of Paris exemplifying precisely because of the plastic transformation of the forms conducted through the exercise of analytical cubism. Ghisetti tends to show the object in its many aspects, analyzing in all its parts, compacting the matter of bodies in volumetric geometries.

Maternity (Figure 10) highlights all the specific elements of the cubist contraction, also emphasizing the expressive value through a chromatic dynamic of futuristic origin.

And at this point, it is worth looking at the same theme that he faced many years ago. Then it was to summon the imperturbability of a moment, the serenity of the child who feeds on the mother's breast. Seeing in the iconography a set of meanings and contents close to the "Madonna with child" of the fifteenth century rather than relevant to the " color irregularities and cubist decompressions of the latest research.

At this stage, the chromatic values that move toward decisive and metallic timbres are enhanced by shaping the characters of those who accumulate energy ready to explode in an insistent dynamism as in the Survival framework (Figure 11).

Perhaps this is the most successful example of a set of solutions (from the futuristic movement to the multiplicity of cubist planes) that express the human bewilderment of violence through a highly suggestive plastic content and synthesis. The bodies, with the irreversible force of their dynamism, disrupt the surrounding environment by generating space-time redundancies that seem to drag them outside the picture.

With a different tenor, almost as if to suppress the tightening of certain human forms, Ghisetti moves with fairytale strokes from curvilinear rhythm, fairy-tale landscapes. This is, as in Summer Landscape, The Crossroads or The Road, a new moment in the artist's painting. Now the shapes do not undergo the geometric cadence typical of Cubism but they soften, flex docile without regard to any prospective linearity, expand by increasing volume and surfaces no longer narrow and spacious but concentric and undulating. The pictorial matter becomes denser, the most visible and briefly painted trait, transfiguring the real in visionary hints of expressionist character. In this context Ghisetti inserts one or more human figures which, as in the Meta picture (Fig. 12), are hypnotic attracted by the concentric movement of the sun to an ideal spiritual world.

It is, however, a painting that does not respect the reality, which does not reproduce the objective nature of things but tries through an authentic and original commitment to seize the most secret and subtle relationships that bind the human being to the world understood as power creative. If the series of self-portraits seemed to embody an existential need that unites all men, that is to ask questions about the meaning of life, their destiny, the meaning of faith, about religion, now with the most recent paintings the artist hangs full confidence in nature and in its unfathomable secrecy.

With the work of the last few years, Ghisetti wants us to say that man alone is unable to solve the great paradigms of existence, which even the human being is too often oriented to cultivate the most detrimental aspects of life. This valid for us all in the example of the Holocaust whose expressiveness degenerates into a cry of pain missed in the eternal, almost to stigmatize the universal and unrepeatable character of that event.

In short, Ghisetti alternates the existential events of modern man by exemplifying the duplicity of his action.

On the one hand the intentionality of evil, overwhelmingness and cruelty; on the other hand, peaceful understanding, solidarity and trust in the future. These are two aspects that belong to the human being, and Ghisetti has perhaps metaphorically portrayed with two subjects (Day and Night and Sacred and Profane) that might suggest the presence in human behaviors in lights but also in shadows.

Through his paintings most filled of hope (Colombe, Together, Dance and all the series of landscapes, including the latest in order of time: Colle Santa Lucia, Spring and Enchanted Wood) we believe that the Murano artist contributes and wishes himself 'approximately of an age that is as little as possible marked by misunderstanding and misguidance. If in the seventies and eighties the forms obtained by homogeneous surface exhumation crystallized the events in an indefinite temporality.

Now Ghisetti's works accentuate the purpose of life, widen the dynamic space, and in viewing the figures we no longer find their evanescence but he animated heat that renews Their existence.

Michele Beraldo

Paesaggio collinare

L'amante orientale

Amanti a Venezia

My World

Incomunicabilità

natura morta con carte da gioco

Sopraffazione

Alleluia

.

La secca

Solare

Le opere di Giampaolo Ghisetti splendono di evanescenza, quasi che una nebbia radioattiva lasci un velo ed un’illuminazione di memoria e sentimento.

Le figure si sfaccettano dunque e riverberano di echi, in un reiterarsi di sagome e movimenti, nel cascare di tono in tono lungo tagli di diamante, si ripercuotono in vibrazioni di piani geometrici che si compenetrano .

Più che la rappresentazione di un moto fisico, queste scomposizioni e ricomposizioni danno il senso degli impeti dell’anima, sono il proiettarsi del sentimento, il suo definirsi persovrapposizioni,

il suo preciso sfalsarsi.

Francesco Giulio Faraci

Ragazza e colombe

Doves

Alberi colorati

Boschetto

Bosco incantato

Pioppi

Metamorfosi

The Giampaolo Ghisetti’works shine with evanescence, as if a radioactive fog leaves a veil and an illumination of memory and feeling.

The figures are thus faceted and reverberate in echoes, in a repeat of silhouettes and movements, in the cascading of tone in tone along diamond cuts, they affect the vibrations of geometric planes that penetrate.

More than the representation of a physical motion, these decompositions and re-compositions give the sense of the impetus of the soul, are the projecting of feeling, its being defined by overlapping, its precise splintering.

Francesco Giulio Faraci

Fanciulla con gatto

Alberi

Notturno in laguna

La serenata di Arlecchino

Alberi colorati

Nel Bosco

Composizione alberata

Composizione con alberi

Primavera

Alberi fantasiosi

Dance

Dal boschetto

Primavera

Temporale in collina

Bivio

Alberi

Family

Casolare in collina

Boschetto

Pianura

Paesaggio estivo